What's eating rural India?

With low crop prices and wages, cash transfers can only provide short-term relief to the rural economy

The slower rise in minimum support prices has placed farmers in a tricky situation

The slower rise in minimum support prices has placed farmers in a tricky situationImage: Tim Graham / Getty Images

In the decade leading up to 2014, rural India had it good. Prices of its main produce—agricultural commodities like wheat, rice and mustard—rose by an average of 12 percent a year. The world’s largest public works programme under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) ensured that men and women received a fair wage for their labour. And a real estate boom saw capital values of agricultural land and homes rise, contributing to a wealth effect across rural India.

MGNREGA wages and increases in crop prices transferred, on an average, ₹1 lakh crore a year to the rural economy and fuelled, primarily, consumption spending. For Hindustan Unilever, the country’s largest consumer products company, rural sales, which make up 38 percent of overall sales, grew by 1.5 times urban sales between 2011 and 2018. Buoyed by this, the company put in place a plan to triple its direct distribution reach.

Two-wheeler maker Hero MotoCorp launched a separate vertical in 2008 to cater to first-time buyers in rural India, as did its four-wheeler counterpart Maruti. Tractor sales, which had contracted 7.5 percent between 1997 and 2004, rose by 10.5 percent a year in the decade to 2014, according to the Tractor Manufacturers Association.

Five years on, the shortcomings of the decade-long boom that ended in 2014 are clear to see. Each of rural India’s growth drivers has come unstuck and farmer protests have got policymakers to pay attention to the causes of rural distress, with the immediate response being two-pronged: Fixing farmers’ balance sheet in the form of loan waivers, and improving their profit and loss account through cash transfers.

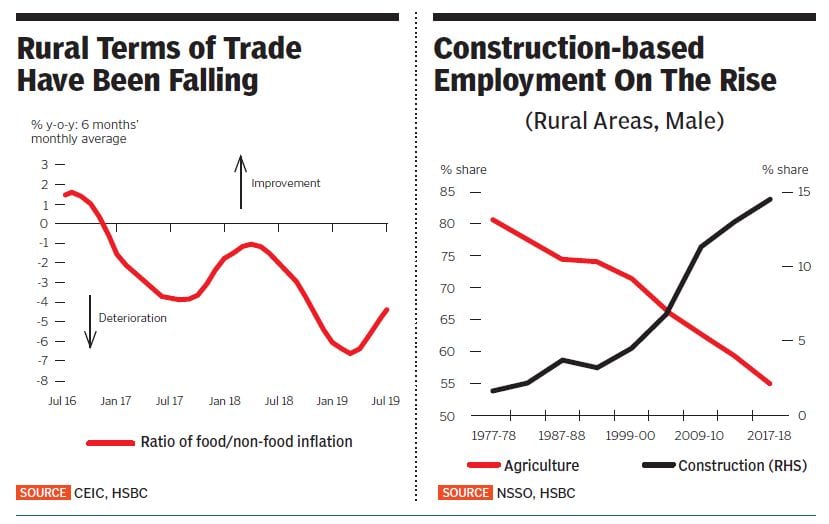

Economists agree that the terms of trade have decisively shifted against rural India. “What we saw was an unprecedented transfer to the rural economy that raised incomes and fuelled food price inflation. Post 2014, a clear policy decision was taken to control food prices,” says Sachchidanand Shukla, chief economist at Mahindra & Mahindra. As a result, increase in state-mandated crop prices was muted.

The Boom

The seeds of India’s increasing crop prices were sown in a global boom of agricultural commodities. Starting 2002, global prices of rice, wheat and maize began rising. Between 2000 and 2007, the Food Price Index—it comprises meat, cereals, dairy, vegetable oils and sugar—collated by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) rose by 50 percent in real terms and doubled in nominal terms. A large part of the price rise was because of higher energy prices that increased input costs of diesel and fertilisers. This continued till 2013.

Indian agri prices, which are benchmarked to both global prices and input costs, also rose sharply. Between 2005 and 2013, paddy prices moved from ₹590 a quintal to ₹1,310 a quintal, an annual increase of 10.4 percent; the price of wheat rose by 10.7 percent a year.

In addition to rising crop prices, the rural economy received another boost through MGNREGA. A big reason for its success was the high wages it initially paid to workers. According to the Periodic Labour Force Survey, in 2007, wages were 5 percent more than market rates. “Wages till 2013 grew at 7 to 8 percent a year for rural India,” says Himanshu, associate professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University, adding that construction jobs accounted for a large percentage of the rise in rural employment. According to him, the rural consumption boom was primarily financed by higher wages till the rate of growth collapsed in 2014.

The Collapse

In mid-2014, the collapse of global oil prices brought about a decline in food prices. The FAO’s weighted basket of various agri products fell by 13 percent in 2014, resulting in slower growth in minimum support prices (MSPs). For instance, the annual growth rate of the MSP for rice fell to 5.5 percent between 2013 and 2019.

The slower rise in MSPs placed Indian farmers in a tricky situation. This was because while global oil prices fell, in India, the input costs did not fall as much as the government refused to lower diesel prices in step with international rates. Farmers’ margins began to get squeezed, and they began to produce more to compensate for lower prices, thus resulting in a glut.

“The lower rise in MSPs moved the terms of trade away from rural India in favour of the urban consumer, but it was in any case a stop-gap solution as it didn’t benefit the landless poor,” says Sujan Hajra, chief economist at Anand Rathi Securities. “For a sector that contributes 15 to 16 percent to the GDP but employs half the workforce, other solutions need to be found.”

At the same time MGNREGA wages declined. By 2011-12, they had become lower than market wages, and by 2017-18, market wages were higher by 74 percent for male workers and 21 percent for female workers. The fact that there is still demand for work under MGNREGA at these reduced wages brings us to the collapse in construction as an important driver of employment in rural India.

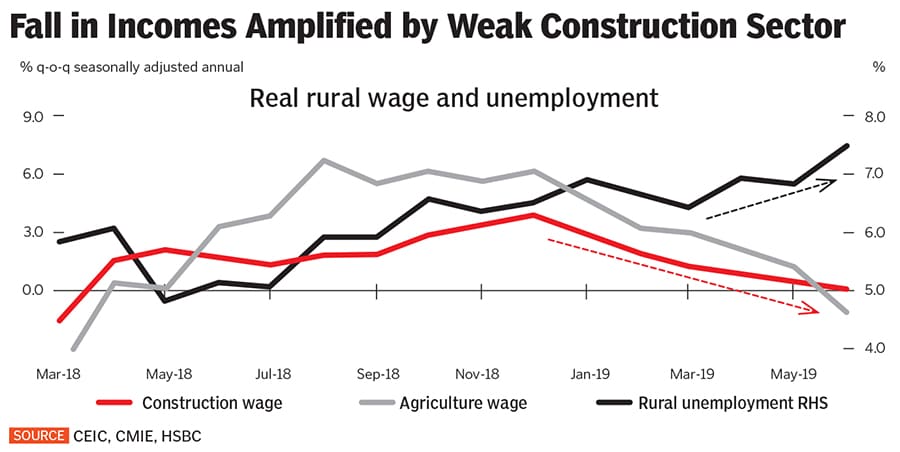

In a 2019 report titled ‘India’s unlikely growth linkages’, HSBC shows how the collapse of construction in both urban and rural India has resulted in a downward pressure on rural wages. “Indeed, rural wages experienced a steeper slump after the NBFC slowdown and the real estate slowdown in end-2018.”

Is Cash the Solution?

From 2017, farmers started agitating for better crop prices as well as waivers on loans. The most prominent was an agitation in Mandsur, Madhya Pradesh, in June that year where six farmers were killed in police firing, prompting the government to come up with measures to reduce rural distress.

In the short term, the government has decided on cash transfers as the best way to placate farmers. In the 2019 interim Budget, it announced the Pradhan Mantri Kisan scheme, under which it promised ₹6,000 a year to farmers owning up to 2 hectares of land; 70 million beneficiaries were identified and 63 million received an instalment of ₹2,000 by March 31. In addition, state government schemes in Telangana and Odisha have also transferred cash to land holders. The Pradhan Mantri Kisan scheme is expected to cost the governmet ₹90,000 crore, while Telangana’s Ruytu Bandhu is budgeted at ₹10,000 crore.

Himanshu, who has tracked rural wages for a decade, says at the most these cash transfers will provide a short-term boost to consumption, while straining government finances. This is also likely to prompt a much-needed return of food price inflation. “There are other ways to keep food price inflation in check, including direct crop subsidies that absorb a part of the production cost,” he says. Shukla believes the money being transferred would have been better spent in improving yields or creating assets like rural roads and houses.

In the absence of increased investment in rural India, cash transfers can serve as a short-term palliative. In real terms, lower creation of assets such as irrigation and cold storage infrastructure, and better quality seeds have resulted in lower income growth. Another problem has been the lack of export opportunities for agricultural produce. As of now, during times of surplus production, the export window is opened on an ad hoc basis. This makes it difficult for India to be seen as a reliable supplier. In 2016, the government had spoken about doubling farmer incomes, primarily from allied activities such as horticulture, organic farming and services, in addition to agriculture. This would again require an upping of investment.

For now, a return of pricing power for farmers looks unlikely. In both real and nominal terms, global food prices have stagnated since 2010, according to FAO, indicating that lower income growth is here to stay in rural India. In the medium term, construction employment could pick up to provide a filip to wages. In the absence of longer-term asset creation, expect more short-term palliatives in the form of cash transfers and loan waivers.

(This story appears in the 27 September, 2019 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)